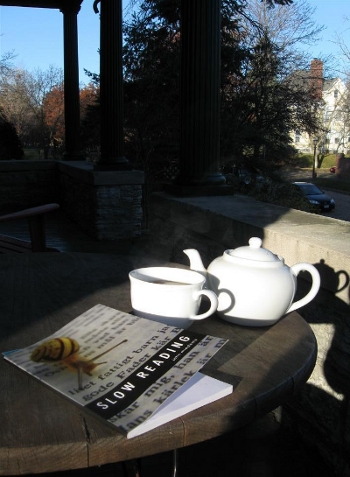

When given the opportunity to read a book with a snail on the cover, it felt important to honor the creature who so elegantly expresses the idea of slowness. I decided to do this by reading the book at a leisurely pace over the course of several weeks. The four essays that make up the book add up to just over 65 pages and one could probably read the whole book in one sitting. However, that seemed like an inconsiderate approach. After all, the author Mr. Miedema states in the Preface and Overview, “Slow reading is about reading at a reflective pace” (p. 1). And so I stepped away from my laptop, ignored my lengthy “To Do List”, and went outside with a freshly brewed pot of tea to start this reflective journey.

I read the first essay about “The Personal Nature of Slow Reading” while enjoying some late fall sunshine and a cup of tea. Another day, I took the book to a park to read the second essay about “Slow Reading in an Information Ecology.” And to celebrate the end of the book, I took it with me to a museum, where I finished the third essay about “The Slow Movement and Slow Reading” while enjoying coffee in the café. After wandering through a few galleries to see if I could adapt his ideas to “slow looking,” I found a chair near a portrait of a scholar and read the fourth essay about “The Psychology of Slow Reading.” Even after finishing the conclusion, I found myself reading the “References” section carefully. The combination of the whimsical cover image, the author's compelling research, and the pleasure of slow reading itself made me want to extend the experience a little longer.

The “References” section of Slow Reading is one of the highlights of this slim volume. It includes citations for articles from traditional library magazines and journals, works of non-fiction by biologists and futurists, and even a Reader's Digest article from 1973. In short, it is a reference list that celebrates a wide range of reading sources. The author, who works as an IT Specialist for IBM, performed research about the topic of slow reading as part of an independent study course in a Master of Library and Information Science program. The extensive list of references and the academic tone of the essays attest to the fact that the book began as homework. Readers are lucky that a publisher encouraged Mr. Miedema to turn the project into a book, and his work has already been noted by one of the United State's foremost cultural institutions, the Library of Congress. In October 2009, the author participated in a one-day conference about “The Future of Reading” that was sponsored by the Federal Library and Information Center Committee, which is part of the Library of Congress (http://www.loc.gov/flicc/FliccForum/2009/forumcall.html). Mr. Miedema's web site has links to the text of his presentation and the handout he developed for the event (http://johnmiedema.ca/2009/10/22/slow-reading-at-flicc-library-of-congress-speech-handout-reference/).

In each essay, the author briefly describes the research he has unearthed about slow reading as it relates to each essay's main topic. For example, the first chapter traces the tradition of slow reading from religious scholars to contemporary academic practitioners of New Criticism. As he does in the subsequent chapters, the author also describes research from other disciplines and reflects about the practice, application, and value of slow reading. At the end of the first chapter, he describes the work of educators who engage youth in reading difficult texts by using student led discussions and performance reading. In other chapters, he describes the recent “Slow Food” movement and the rise of local eating before proposing that libraries pursue a similar goal by promoting local reading. He also draws on evidence from neuroscience to highlight the importance of giving our brains time to process what we read. As a reader, I was intrigued by Mr. Miedema's interdisciplinary research. Several of the works he cited are now on my ever-growing list of things to read.

In the second chapter, which happens to be the longest, the author presents a balanced discussion about the value and challenges of digital information. Although he highlights the differences between consuming information online and reading print, he does so without directly comparing them. I especially appreciated his call for people themselves to slow down, rather than blaming our information overload on technology:

“Reading is connected to literacy and critical thinking, but digital technology is not the primary villain. The real problems are our weakness for speed and our attempts to attend to too many things at once. We cannot accelerate our lives indefinitely. At some point we have to slow down to get a handle on our information. Slow reading represents balance.” (p.31)

As a reader, I appreciated these digressions from strictly academic prose. Mr. Miedema has an engaging writing voice, and I enjoyed reading his own arguments and ideas after considering his summaries of other researchers' work.

He contends that libraries are thriving in this “information ecology” because they offer a wide range of materials and services, plus librarians who value providing access to information. According to the author, “It is no wonder that libraries have thrived through the digital age. They are one of the few places that respond to the complexity of our information needs.” (p. 39). This is a powerful statement in support of libraries, and I imagine that this section will resonate with readers who currently work in library settings.

When I finished the book, I was surprised to find that the author had decided to include an index. Since the book is modest in terms of length and is focused on a specific set of topics, I did not feel that the index was a useful addition to the book. In fact, I would have preferred reading an essay about one of the author's own slow reading experiences. Index or no index, dedicated readers and anyone who cares about literacy and libraries would be well-served by reading this book. I encourage those who pick it up to be inspired by the snail on the cover and the author's own research before indulging in a bit of slow reading with this book.

Caralyn Champa is a recent graduate of the Master of Library and Information Science program at St. Catherine University in St. Paul, Minnesota. She is currently seeking opportunities to work as a librarian in the Obama administration.